Parampara is knowledge that is passed in succession from teacher to student. It is a Sanskrit word that denotes the principle of transmitting knowledge in its most valuable form; knowledge based on direct and practical experience. It is the basis of any lineage: the teacher and student form the links in the chain of instruction that has been passed down for thousands of years. In order for yoga instruction to be effective, true and complete, it should come from within parampara.

Knowledge can be transferred only after the student has spent many years with an experienced guru, a teacher to whom he has completely surrendered in body, mind, speech and inner being. Only then is he fit to receive knowledge. This transfer from teacher to student is parampara.

The dharma, or duty, of the student is to practice diligently and to strive to understand the teachings of the guru. The perfection of knowledge – and of yoga — lies beyond simply mastering the practice; knowledge grows from the mutual love and respect between student and teacher, a relationship that can only be cultivated over time.

The teacher’s dharma is to teach yoga exactly as he learned it from his guru. The teaching should be presented with a good heart, with good purpose and with noble intentions. There should be an absence of harmful motivations. The teacher should not mislead the student in any way or veer from what he has been taught.

The bonding of teacher and student is a tradition reaching back many thousands of years in India, and is the foundation of a rich, spiritual heritage. The teacher can make his students steady – he can make them firm where they waver. He is like a father or mother who corrects each step in his student’s spiritual practice.

The yoga tradition exists in many ancient lineages, but today some are trying to create new ones, renouncing or altering their guru’s teachings in favor of new ways. Surrendering to parampara, however, is like entering a river of teachings that has been flowing for thousands of years, a river that age-old masters have followed into an ocean of knowledge. Even so, not all rivers reach the ocean, so one should be mindful that the tradition he or she follows is true and selfless.

Many attempt to scale the peaks in the Himalayas, but not all succeed. Through courage and surrender, however, one can scale the peaks of knowledge by the grace of the guru, who is the holder of knowledge, and who works tirelessly for his students.

Shri Tirumal ai Krishnamacharya

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya – yogi, healer, linguist, Vedic scholar, expert in the Indian Schools of thought, researcher, author… in other words, a legend. Born in 1888 in a remote Indian village, T Krishnamacharya who lived to be over hundred years old was one of the greatest yogis of the modern era.

Tirumalai Krishnamacharya – yogi, healer, linguist, Vedic scholar, expert in the Indian Schools of thought, researcher, author… in other words, a legend. Born in 1888 in a remote Indian village, T Krishnamacharya who lived to be over hundred years old was one of the greatest yogis of the modern era.

If today, yoga is an inherent part of the everyday lives of millions of people across the world, it is due in large measure to the pioneering efforts of T. Krishnamacharya who revived yoga in the early twentieth century. While preserving ancient wisdom and reviving lost teachings, Krishnamacharya was also a revolutionary innovator who developed and adapted yoga practices that were as would offer health, mental clarity and spiritual growth to any individual in the modern day world.

Krishnamacharya’s knowledge of yoga was so vast that he taught each student differently. In refusing to standardize the practice and teaching methodology, Krishnamacharya created an understanding of yoga relevant for a broad spectrum of students. By integrating the ancient teachings of Yoga and Indian philosophy with modern-day requirements, Krishnamacharya created yoga practices that are as accurate and powerful as they are practical and relevant.

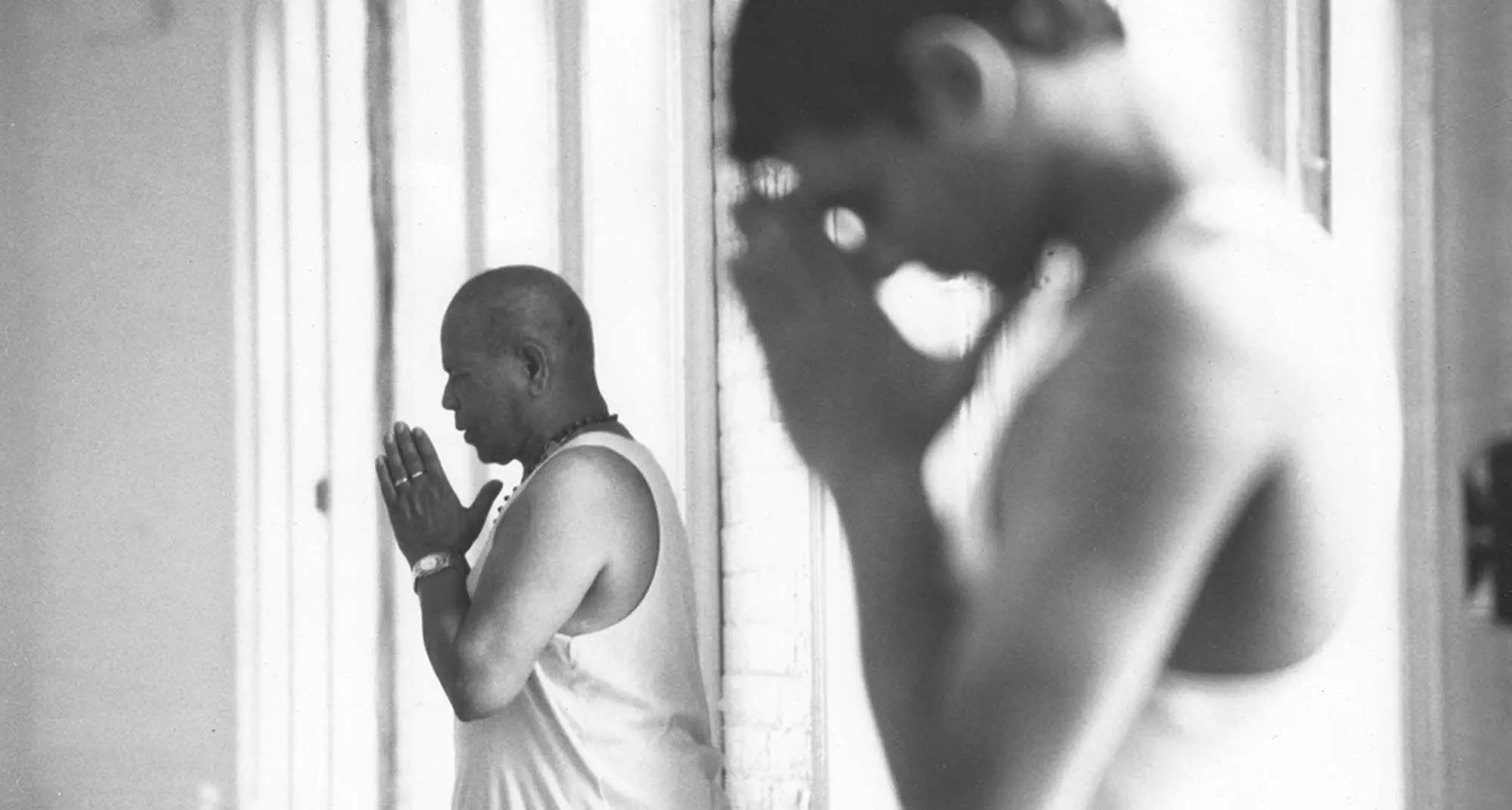

Shri K. Pattabhi Jois

Yogacharaya Shri K. Pattabhi Jois (Guruji) was born on the full moon of July 1915, in Kowshika, a small hamlet located 150 kilometers from Mysore in the southern state of Karnataka. His father was an astrologer and a priest in the village of nearly seventy families. Guruji was the middle of nine children, and from the age of five, like most Brahmin boys, began to study the Vedas and Hindu rituals. At 12, he attended a yoga demonstration at his middle school that inspired him to learn more about the ancient practice. He was so excited about this new discovery, he arose early the next morning to meet the impressive yogi he had seen, Sri T. Krishnamacharya, one of the most distinguished yogis of the 20th Century.

Yogacharaya Shri K. Pattabhi Jois (Guruji) was born on the full moon of July 1915, in Kowshika, a small hamlet located 150 kilometers from Mysore in the southern state of Karnataka. His father was an astrologer and a priest in the village of nearly seventy families. Guruji was the middle of nine children, and from the age of five, like most Brahmin boys, began to study the Vedas and Hindu rituals. At 12, he attended a yoga demonstration at his middle school that inspired him to learn more about the ancient practice. He was so excited about this new discovery, he arose early the next morning to meet the impressive yogi he had seen, Sri T. Krishnamacharya, one of the most distinguished yogis of the 20th Century.

After questioning Guruji, Krishnamcharya agreed to take him on as his student, and for the next two years, unbeknownst to his family, Guruji practiced under the great yogi’s strict and demanding tutelage every day before school, walking five kilometers early in the morning to reach Krishnamacharya’s house. He was ambitious in his studies and driven to expand his knowledge of yoga. When he would read the Ramayana and other holy books on the veranda of his house, his family members would say, “Oh, look at the great pundit. Why are you wasting your time with books? Go tend to the cows!”

Mysore

When Guruji turned fourteen, he was given the Brahmin thread initiation – the ceremony in which a Brahmin boy becomes a man and is initiated into the spiritual life. Soon after the significant ceremony, and with two rupees in his pocket, Guruji secretly ran away from home to seek Sanskrit study at the Sanskrit University of Mysore. After getting off the train, he went straight to the admissions department, showed his thread as proof of being Brahmin [this would gain him free admission], and was accepted to the school. He dutifully attended classes and his studies, and continued his yoga practice, even giving demonstrations that secured him food privileges at the university mess. With little money, life in the beginning was difficult for Guruji, who also begged for food at Brahmin houses. It was three years before he wrote to his father to tell him where he was and what he was doing.

In 1932, he attended a yoga demonstration at the university and was pleased to discover that the yogi on stage was his guru, Sri Krishnamacharya. Having lost touched after Guruji left Kowshika, they recommenced their relationship in Mysore, which lasted twenty-five years.

The Maharaja

During this time, Mysore’s Maharaja, Sri Krishna Rajendra Wodeyar, fell suddenly ill. Informed of a remarkable yogi who might help him where all others had failed, he sent for Krishnamacharya, who cured him through yoga. In gratitude, the Maharaja established a Yoga shala for him on the palace grounds, and sent him, along with model students like Guruji, around the country to perform demonstrations, study texts, and research other yoga schools and styles. Some one hundred students were schooled at the palace yoga shala.

The Maharaja was especially fond of Guruji and would call him to the palace at four in the morning to perform yoga demonstrations. In 1937, he ordered Guruji to teach yoga at the Sanskrit University, in spite of his desires to remain a student. Guruji established its first yoga department, which he directed until his retirement in 1973. The department was permanently closed after that.

The Maharajah died in 1940, bringing an end to Krishnamacharya’s long patronage. By the time the esteemed teacher left for Madras in 1954, he had only three remaining, very dedicated students: Guruji, his friend C. Mahadev Bhatt, and Keshavamurthy. Guruji was the only one who considered teaching his life’s work, and carried on Krishnamacharya’s legacy in Mysore.

Family

While Guruji was studying with Krishnamacharya, a young and strong-willed girl began to attend his yoga demonstrations at the Sanskrit University, accompanied by her father, a Sanskrit scholar. One day, after one of the demonstrations, Savitramma, who was only fourteen at the time, announced to her father, “I want that man in marriage.” Agreeably, her father approached the 18-year-old Guruji and invited him to their home in the village of Nanjangud, twenty kilometers away. Guruji respectably accepted. After learning more about the young yogi and his Brahmin and family background, Savitramma’s father agreed to the union, as did Guruji’s father despite the couple’s horoscope report of unsuitability. “Suitable or not, I want to marry him,” declared Savitramma, who later came to be affectionately known as Amma [mother]. They were married that year in a love match on the fourth day after the full moon of June 1933, Amma’s birthday.

After the wedding, Amma returned to her family and Guruji to his room at the University. They didn’t see each other for three to four years, until 1940, when Amma joined her husband in Mysore to begin their life together. They had three children – Manju, Saraswathi and Ramesh – each who became great yoga teachers themselves. Amma was Guruji’s first yoga student, and was also given a teaching certificate by Krishnamacharya. Amma was like a mother to Guruji’s students, both Western and Indian; her presence cherished as much as his. She was kind and loving, always ready with an invite for coffee or an encouraging word. Because she was also well-versed in Sanskrit, she was often nearby to correct Guruji’s mistakes or remind him of a forgotten Sanskrit verse – much to the amusement of all present. She passed away suddenly in 1997. Her loss was devastating to the entire family, as well as to the family of yoga students.

Teaching

Life during the early years was not easy. Although Guruji had a yoga teaching position at the Sanskrit University, his ten-rupee-a-month salary was barely adequate to maintain a family of five. [Their circumstances eased somewhat in the mid-fifties when he became a professor.] In 1948, Guruji established the Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute in their tiny two-room home in Lakshmipuram with a view toward experimenting with the curative aspects of yoga. Many local officials, from police chiefs to constables and doctors, practiced with him. Local physicians even sent their patients to Guruji to help with the treatment of diabetes, heart and blood pressure problems and a variety of other ailments.

In 1964, Guruji added an extension to the back of his house, consisting of a yoga hall that held twelve students, and a resting room upstairs. That same year, a Belgian named Andre van Lysbeth arrived at the AYRI on the recommendation of Swami Purnananda, a former student of Guruji’s. For two months, Guruji taught this foreigner the primary and intermediate asanas. Soon after, Van Lysbeth wrote a book called Pranayama in which Guruji’s photo appeared, and introduced the Ashtanga master to the Europeans. They eventually became the first Westerners to seek him out and study in Mysore. Americans followed soon after in 1971.

Guruji had already traveled widely in India with Krishnamacharya and with Amma, meeting yogis, debating with scholars and giving yoga demonstrations. He met with Swami Sivananda, and the Shankaracharya of Kanchipuram, and befriended Swami Kulyananda and Swami Gitananda, both renowned for their scientific research in yoga. Guruji’s ashtanga had extended throughout India, but didn’t reach the overseas community until 1973 (the very same year he retired from the Sanskrit University), when he was invited to Sao Paulo, Brazil. The following year he went to Encinitas, California, the first of many teaching trips abroad, including France, Switzerland, Finland, Norway, England and Australia.

Over the next twenty years, word of Pattabhi Jois and ashtanga yoga slowly spread across the globe, and the number of students coming to Mysore steadily increased. In 1998, Guruji shifted his residence to Gokulam, a suburb of Mysore, but continued teaching from the Lakshmipuram institute. By then, he was receiving more international students than the small room could handle, so he began construction of a much larger hall, just opposite his house in Gokulam. The new shala officially opened in 2002, with several days of pujas and ceremonies. Four years later, his dream of opening a school in the United States was realized with the launch of an institute in Islamorada, Florida. Guruji conducted the opening ceremonies there in 2006, which served as his final trip abroad.

The Passing of the Lineage

In 2007, Guruji became gravely ill, bouncing back just enough to teach a bit more yoga. By the end of the following year, after seven decades of continuous teaching, he had gradually retired from his daily classes, leaving the institute in the capable hands of his daughter Saraswathi and grandson Sharath.

Guruji passed away at home in Mysore on May 18th, 2009 at the age of 93. His death came as a tragic loss to the worldwide yoga community. His entire life was an endeavor to imbue his students with commitment, consistency and integrity – and to actualize in his own life the conduct of a householder yogi. It is by virtue of his undying faith and enthusiasm that the practice that he learned from Krishnamacharya has remained alive. And thus, by his devotion to the daily teaching of yoga, his legendary works will remain alive too.

R. Sharath Jois

Sharath was born on September 29, 1971 in Mysore, India to Saraswathi Rangaswamy, daughter of ashtanga master Sri K. Pattabhi Jois. Growing up in a house full of yoga practitioners, Sharath learned his first asanas at age seven and experimented with postures from the primary and intermediate series until he turned fourteen. Though he spent the next three years focused on his scholastic education, earning a diploma in electronics from JSS in Mysore, Sharath knew that he would one day follow the ashtanga path blazed by his mother and legendary grandfather.

Sharath was born on September 29, 1971 in Mysore, India to Saraswathi Rangaswamy, daughter of ashtanga master Sri K. Pattabhi Jois. Growing up in a house full of yoga practitioners, Sharath learned his first asanas at age seven and experimented with postures from the primary and intermediate series until he turned fourteen. Though he spent the next three years focused on his scholastic education, earning a diploma in electronics from JSS in Mysore, Sharath knew that he would one day follow the ashtanga path blazed by his mother and legendary grandfather.

Sharath embarked on his formal yoga study at the age of nineteen. He would wake every day at 3:30 a.m. and cross the town of Mysore to his grandfather’s Lakshmipuram yoga shala. There, he would first practice and then assist his guru, Pattabhi Jois, a routine of dedication he has followed for many years.

Today, Sharath’s sincere devotion and discipline to the study and practice of yoga compels him to rise six days a week at 1:00 a.m. to complete his practice before the first students arrive at the K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute, where he serves as Director.

Sharath is Pattabhi Jois’s only student who has studied and continues to practice the complete six series of the ashtanga yoga system. He presently resides in Mysore with his wife Shruthi, daughter Shraddha, and son Sambhav.

R. Saraswati

Born in 1941 to Savitramma and yoga master, K. Pattabhi Jois, Saraswathi played with yoga postures at an early age. At 10, she began her formal study of ashtanga yoga under the guidance of her father, and eventually became the first woman admitted to the Sanskrit College in Mysore, where she studied Sanskrit works and yoga.

Born in 1941 to Savitramma and yoga master, K. Pattabhi Jois, Saraswathi played with yoga postures at an early age. At 10, she began her formal study of ashtanga yoga under the guidance of her father, and eventually became the first woman admitted to the Sanskrit College in Mysore, where she studied Sanskrit works and yoga.

At the age of twenty-two Saraswathi’s mother became ill and Saraswathi took on all household responsibilities along with caring for her mother, father, and younger brothers. Leaving aside her asana practice, Saraswathi grew strong in other areas of yoga. In 1967, she married M.S. Rangaswamy and had two children, daughter Shammi in 1969 and son Sharath in 1971.

Saraswathi assisted her father at his Lakshmipuram yoga shala from 1971 until 1975. She then began teaching yoga to local Indian women on her own at the Balaji Temple in V.V. Mohalla. At the time, yoga teachers were treated no differently than the cleaners and sweepers of the temple grounds and she was paid only twenty fives rupees a month. In 1984, she began teaching yoga to both men and women together in her own house in Gokulam.

When her father moved his Ashtanga Yoga Research Institute from Lakshmipuram to Gokulam in 2002, Saraswathi returned to teaching with her father. Today, she is a constant presence at the K. Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Yoga Institute. Saraswathi welcomes all yoga students who come to Mysore.

www.kpjayi.org